In April of 1957 in the forests of what is now Cameroon, a female chimpanzee forages with her troop while, across the continent in Kenya, a young English woman first sets foot in Africa. The rainy season is coming, and around July, the female chimpanzee will give birth to a baby boy. We can’t know whether this is her first baby, but we know she tends him well. She nurses him and holds him and protects him during his vulnerable early life. She is his source of nourishment and his comfort, and his body is in constant contact with hers as she moves through the forest, builds their sleeping nests in the trees. He will be famous, this baby boy, before he is even four years old. The young English woman will be famous, too.

She is Jane Goodall, and she will tell us her story and the stories of the chimpanzees in Tanzania she comes to know and love. At first, she will be shunned as unscientific. She gives the chimps she observes names instead of numbers—David Greybeard and Goliath, Flo and her son Flint. She describes their emotions and personalities. She forces a redefinition of what it means to be human when she observes them making and using tools. Hers is a story many in the scientific community don’t want to hear, but she persists, and over time, she is proven right. Chimps do make and use tools. They have culture. They have personalities and emotions and form deep bonds with others. They are intelligent and self-aware. Even their ability to be deceitful proves they can see a situation from another’s perspective. They can imagine what it is like to be someone else. Just as we can—just as we should as we turn our gaze back to the little chimp.

He will first be known as Subject 65 before eventually being called Ham. He will be the first great ape to be launched into space. And for many years and even still today, this is how his story will be told: that he is an intrepid space hero, an astrochimp, a celebrity. There are some dissenting voices, but they are the exception.

In most reports, there will be a sentence, maybe two, about how he is trapped or caught, or even just “brought” from present-day Cameroon to the Miami Rare Bird Farm, where he is sold in 1959 to the United States Air Force for $457. He is two years old.

The truth is, he is probably his mother’s last baby. In all likelihood, she dies defending him from the animal trappers who capture him—how else could they wrest his little body from hers? According to Project ChimpCARE, baby chimpanzees “will venture a small distance from their mothers at around two years of age and are weaned by their mothers between the ages of four and six. Chimpanzees become independent between six and nine years of age. Although at this age they become much more independent, chimpanzees will have lifelong bonds with their mothers.” But not baby Ham, whose name will come from the acronym for the Holloman Aeromedical Laboratory where he is headed.

![]()

By 1959, when Ham and other young chimps arrive at the Holloman Airforce Base in Alamogordo, New Mexico, the United States has been attempting to send nonhuman animals into space for over a decade. NASA’s “A Brief History of Animals in Space” describes a 1949 launch as follows: “Albert IV, a rhesus monkey attached to monitoring instruments, was the payload. It was a successful flight, with no ill effects on the monkey until impact, when it died.” In the book Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle, the authors describe rocket sled deceleration tests designed to measure the effects of tremendous forces on the bodies of living beings, sometimes human volunteers, but often pigs and chimpanzees: “The animal in question had been anaesthetised and strapped onto the sled in a head-first configuration, blasted down the rails, and brought to an abrupt stop measured at a crushing 270 g’s. One of the researchers would later describe the luckless chimpanzee’s remains as ‘a mess.’”

The US is desperate to beat the USSR in launching a human into space; both countries treat nonhuman animals as tools in their frenzied race while referring to them as “partners” or “fellow astronauts.” A 1967 US Air Force film even claims the chimps benefit from their arrival at Holloman: “The chimpanzees are purchased from dealers who import them from the jungles of equatorial Africa. And frequently their physical condition is less than satisfactory … Here, they are treated with the professional care accorded human patients in a modern hospital and often gain their first insight into the basic kindness of their fellow primate—man.”

Here is the basic kindness Ham experiences at Holloman. Instead of just beginning to venture out from the safety of his mother’s arms, to which he could have returned again and again when frightened, and instead of observing his mother making and using tools or tasting the fruit she forages, Ham is being taught instead by his trainers. Just as his movements in the wild would have begun to increase, his movements in the laboratory become more and more restricted. According to Animals in Space, the officer in charge of the chimps’ training, Edward Dittmer, described their training as follows: “We started out by teaching them to sit in these little metal chairs set about four or five feet apart so they couldn’t play with each other. We dressed them in these little nylon web jackets which went over their chests and we could then fasten them to their chair. We’d keep them in the chairs for about five minutes or so and feed them apples and other fruit, and we’d progressively put them in their seats for longer periods each day. Eventually they’d just sit there all day and play quite happily.”

The chimpanzees are also forced to endure decompression chamber experiments, as shown in the same US Air Force film—these experiments involve keeping them strapped into small metal capsules called “couches” in a decompression chamber for seven to eight hours before subjecting them to extreme changes in pressure to simulate altitude changes from 35,000 to 150,000 feet. The film notes that after fifteen seconds at the equivalent of 150,000 feet, a young chimp becomes unable to perform his tasks, and it takes almost two and a half hours on average after re-pressurizing the chamber for him to return to his normal working ability. The film goes on to tout the importance of this research and says, “Somehow, one gets the impression, the chimpanzee is proud of his contribution.”

What are the tasks the young chimps are performing, day in and day out? Strapped into their seats, with a ring around their necks to further hold them in place, they are required to push levers based on light cues. If they perform their tasks correctly, they are rewarded with banana pellets or a drink of water. If they fail, they are punished with electric shocks from the metal plates strapped to their feet. These are the tasks Ham will be expected to perform in space when he is chosen, first as one of six candidates out of an initial forty, and then as the preferred candidate out of the six, to be launched into suborbital flight in the nose cone of the Mercury Redstone-3 rocket. Why is he chosen? For his physical condition, but also for his friendliness, for being so agreeable. Number 46, a young chimpanzee named Minnie, is his back-up. Again in Animals in Space: “‘I had a great relationship with Ham,’ Dittmer recalls with obvious fondness. ‘He was wonderful; he performed so well and was a remarkably easy chimp to handle. I’d hold him and he was just like a little kid. He’d put his arm around me and he’d play.’”

The following is compiled from detailed accounts on NASA’s website, including the report entitled “Results of the Project Mercury Ballistic and Orbital Flights.” On January 31, 1961, Ham is awakened at approximately 1 a.m. After being subjected to various tests and exams, during which researchers implant electrodes under his skin and insert a thermometer eight inches into his rectum, taping it in place, his handlers strap him into his couch at 2:03 a.m. and move him to a transfer van. At 3:02 a.m., he is fed eight ounces of a low-residue diet, and his couch is sealed up. Three hours later, they load him into the Mercury Redstone-3 rocket nose cone.

Almost immediately, systems and components—five of which are new in Ham’s capsule and have not yet been tested in prior flights—begin to malfunction. Although take-off is scheduled for 9:30 a.m., multiple issues arise, the most serious of which is an electronic inverter in the capsule that overheats again and again each time the power is turned back on after a cool-down period. The rocket has to launch before noon in order to give the recovery ships enough time before dark to make sure they can find Ham after splashdown. At 11:55 a.m., hours after Ham is loaded into the spacecraft and with the electric inverter still overheating and five foot waves reported in the area where splashdown is expected, Ham is launched into space.

Within a minute of launch, it is apparent that, similar to the previous Mercury launch, the flight path angle is too high, the acceleration is too great, and Ham will experience 17 g’s of force instead of the predicted 9 g’s. Modern astronauts experience about 3 g’s during launch. Since Ham weighs 37 pounds, he experiences such force and pressure on his body, he feels as though he weighs almost 630 pounds. He manages to mostly perform his tasks—receiving one shock at the beginning of his flight, which it turns out was a malfunction, since he has pushed his lever in time, and one shock during reentry, when he experiences 14.9 g’s and then 10 g’s, but for longer than the 17 g’s during launch.

The unexpected increase in g’s both during launch and reentry are due to a faulty valve, which injects too much liquid oxygen into the engine, where, combined with the fuel, the engine burns hotter than planned, increasing the thrust and therefore the acceleration. It also depletes the liquid oxygen sooner than expected and causes the new closed loop abort system to initiate an abort sequence, which includes jettisoning the retrorockets that would have slowed the capsule down on reentry. Another valve, designed to open after the parachute is deployed, opens prematurely due to vibrations, causing a dangerous drop in cabin pressure within the capsule. The pressure drop is enough that Ham might have suffocated if he had not been sealed into his couch.

When Ham’s capsule lands in the ocean, about 130 miles out of his expected splashdown area, Ham has been in his couch for over ten hours, has survived the 16 ½ minute duration of his flight and experienced 6.6 minutes of weightlessness, but his ordeal is still not over. The heat shield snaps off and punctures the hull. Water begins to pour into the capsule through the holes, as well as through the valve that caused the drop in pressure during the flight. By the time Ham’s capsule is lifted out of the water by helicopter two and a half hours later, it has taken on about 800 pounds of water. Although Ham is saved from drowning because he is sealed into his couch, the researchers do find a small amount of bloody vomit they believe to have been a result of Ham experiencing rough seas in his sinking capsule, and they note his couch is hot and humid inside when opened.

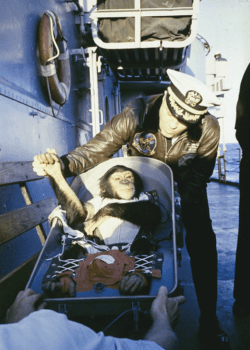

Once the container arrives on the USS Donner, three-year-old Ham can be heard squealing. His vocalizations are not the only evidence we have of the trauma of his ordeal. His physiological data show us that during his flight his heart and respiration rates spike with the g-forces (charts of which can be seen here on page 32, printed on page 28) but remain elevated beyond them. His heart rate is 94 beats per minute the morning of the flight but increases to 126 and then 147 during launch. During reentry, his heart rate reaches 174 beats per minute but during one ten second period his heart beat thirty-four times. His respiration rate ranged from 22 to 72 breaths a minute. And all the time, he pulls his levers in a desperate attempt to avoid shocks to his feet. Even on reentry when his response time slows as his heart and respiration rates spike, he pulls his levers.

Most reports about his space flight want to assure us he is fine. Just a bruise on his nose (a “self-inflicted” abrasion) and a little dehydrated (he’s lost 5.37% of his body weight). He is eager for his apple treat—his appetite isn’t even affected (he hasn’t had anything to eat or drink in approximately sixteen hours). And many articles at the time point to the wide grin on his face. Except that chimpanzees don’t grin with happiness, they grimace in fear. Jane Goodall, in response to seeing a picture of Ham after his space flight, will say, “I have never seen such terror on a chimp’s face.” A terrified three-year-old who cannot retreat to the comfort of his mother’s arms, he is subjected to yet another physical exam and then placed into a small cage on the ship by himself.

According to a report cited on NASA’s website, Ham becomes “highly agitated” and snaps at people when confronted by the crowd of press. He panics when his handler attempts to pose him near the capsule for photographs. According to the report, it takes “three men to calm the ‘astrochimp’ for the next round of pictures.” He will never willingly go near a capsule again, and so a different chimp will have to endure the second and last Project Mercury chimpanzee space flight.

This chimpanzee is Enos, pictured in photographs with a strap tied to his wrist to control him. As Dittmer recalls in Animals in Space, “He was smart but he didn’t take to people … They said he was a mean chimp, but he wasn’t really mean. He just didn’t take to cuddling.”

On November 29, 1961, five-year-old Enos is launched into space for three orbits around the earth, though because of equipment malfunctions within his capsule, he is shocked over and over despite performing his tasks correctly while also suffering the effects of an overheating space suit. The flight is aborted after two orbits due to failing thrusters, and when he is retrieved from splashdown hours after landing, he has removed and destroyed the sensors inserted into his heart and forcibly removed his urinary catheter while the balloon was still inflated. A year later, he will be dead of dysentery.

![]()

And what becomes of Ham? Story after story will refer to his “retirement” to the National Zoo in 1963 at age six, four years after his arrival at Holloman, two years after his space flight, just at the age he would be starting to be more independent from his mother if he had not been taken from her. Just as he would be finding his way in the larger chimp society, in his troop that might number 20 to 150 members, he is instead confined alone in a barren concrete and brick cage at the National Zoo, where he will live in solitary confinement for seventeen years, enjoying what people telling his story call “celebrity status.” After all, he does receive fan mail and has a cameo in an Evel Knievel movie. According to the US Air Force film, he “basks in the glow of his memories amid the peaceful surroundings of the National Zoological Park,” which can be seen here. He does remember his time at Holloman. In a 2010 article in the Smithsonian’s Air & Space Magazine, Melanie Bond, one of Ham’s keepers at the National Zoo, who describes him as a “lonely guy,” recounts Ham’s reaction to having his feet tickled, a decade after he has left Holloman: “One of the things I would ask, was, ‘Do you want me to tickle your toes?’ And he would offer his feet, but he would also seem to be very reluctant, and kind of whimper and cry a little bit…. I would tickle his toes and he would laugh, and he really seemed to enjoy that. Until years later I learned that part of his training involved having his feet strapped on metal plates, and if he didn’t perform the behaviors they wanted him to perform, he would receive an electric shock. That memory stayed with him years after.”

In September of 1980, he is transported to the North Carolina Zoo in Asheboro and spends just over two years in the company of other chimps before dying in January of 1983 at twenty-five years old of liver failure and the heart disease that is the leading cause of death for captive chimpanzees.

After his death, plans to taxidermy his body for display are met with public outrage at what people perceive as disrespect towards Ham. Instead, in a questionably more respectful decision, his skin and flesh are separated from his bones and buried at the International Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo, New Mexico, while his skeleton is given to the National Museum for Health and Medicine. This burial, and people calling him a hero, and the Air Force giving him a salute as he is transported from one zoo to the next, this is how we show him respect. But what does Ham care about fan mail, about a salute, about fame or what happens to his body when he is dead? How is he respected in life? He isn’t. Not when he is torn from his mother as a baby, not when he is sold for for $457, not when he is forced to sit for up to twenty-four hours in a metal chair, not when he is trained to push levers to avoid electric shocks, or when he is launched into space, or left alone in a cage for 17 years at the National Zoo, not even when he is transferred to the North Carolina Zoo “on breeding loan” and has the companionship of other chimpanzees for the first time in almost two decades. Because the only way to respect a self-aware being like a chimpanzee is to respect his autonomy, his right to bodily liberty. And when did he have that? Maybe when humans were unable to force him back into his space capsule after his flight? Maybe when he chose Maggie as his favored companion at the North Carolina Zoo? Is this a respected life?

And how do we respect the other space chimps at Hollomon Aeromedical Center? Those who survive, including Ham’s back-up Minnie, are leased for biomedical research to test the cancer-causing effects of chemicals and to be injected with HIV and other diseases. The man who will control their lives for many years is Frederick Coulston, who has turned to chimpanzees after being forced to stop his 1960s experiments on human prisoners.

Decades later, in 1997, when the US Air Force decides the surviving chimps are “surplus to requirements,” Dr. Carole Noon leads an effort to retire them to sanctuary. Although the US Air Force claims in a 1997 Wall Street Journal article that the “welfare of the chimpanzees will be the main consideration in assessing June’s bid proposals,” they sell them to Frederick Coulston, the same man who has been leasing them and experimenting on them for years and whose facility has repeatedly violated the Animal Welfare Act, leading to the suffering and deaths of its residents.. Minnie dies in March of 1998. She, like Ham and Enos and so many others, will not know freedom. In 2000, the NIH takes over custody of 288 of the chimpanzees under Coulston’s control following a settlement between Coulston and the USDA over the foundation’s animal welfare violations. The chimpanzees are housed at the Holloman Airforce Base primate facility, which had also been under Coulston’s management.

But the tide is turning. Carole Noon sues the US Air Force and in 2000 is awarded custody of 21 of them. By the time she wins her suit, she has founded the first chimpanzee sanctuary in the US, “[enabling] the chimps to roam freely and make basic choices formerly denied to them” and the first chimpanzees from New Mexico arrive at the sanctuary in 2001. By then, the Coulston Foundation is going bankrupt, and in 2002, Dr. Noon is able to purchase the Coulston Foundation’s Alamogordo facility. Since the chimpanzees are no longer of use to the foundation, the 266 chimps remaining in the facility are given to Save the Chimps. These chimpanzees, along with the twenty-one already in Dr. Noon’s custody, including Minnie’s daughter Lil Minnie, will experience sanctuary.

![]()

It is true that captivity for chimps has improved in the six decades following Ham’s capture. The Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which went into effect in 1975, restricting the importation of wild-caught chimpanzees like Ham. Dr. Goodall and other scientists, and of course the chimps themselves, have shown us the emotional and cognitive capacities of chimpanzees, and many zoos and other facilities have worked to provide enrichment and, in some settings, more naturalistic habitats. Biomedical research on chimpanzees has come to an end in most of the world, in part out of a realization of the depths of their suffering in laboratory facilities, but also because science has shown us they are very poor research models for humans, despite sharing over 98% of our DNA, as for example in AIDS research, in which the many chimpanzees injected with HIV do not develop the symptoms of AIDS seen in humans. In 2015, the US finally added captive chimpanzees to their wild counterparts’ endangered listing under the Endangered Species Act, and the National Institutes of Health announced an end to biomedical research on the chimps under their control, including those remaining at the Holloman Air Force Base laboratory, promising to retire all eligible chimps in their custody to sanctuary and financially support them there.

All of these changes are good, yet chimpanzees remain legal things with no more rights than when the Wall Street Journal, in its 1997 description of the battle between Frederick Coulston and those wishing to move the surviving US Air Force chimps to sanctuary, quoted the USAF colonel in charge of divestment: “Chimps—right, wrong or otherwise—are basically personal property. They’re like a piece of equipment.”

According to Project ChimpCARE, as of January 2022, there are approximately 1356 chimpanzees in captivity in the US alone. Six-hundred and eighty-three of them are in sanctuaries accredited by the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries, some of which respect chimpanzees’ autonomy better than others. Two-hundred and thirty-nine live in American Zoological Association-accredited facilities, 136 in unaccredited facilities, 13 are used in “entertainment,” and approximately 19 are held or bred as “pets.” Although possession of chimpanzees is illegal in most states, there is no current federal law against keeping chimpanzees as pets, and there is nothing preventing current welfare regulations from being reversed or weakened in the future.

Even in the more modern, enriched environments of AZA-accredited zoos, chimpanzees do not have sufficient control over their own lives, and so they exert control in the only way they can, through engaging in abnormal behaviors. A 2011 study entitled “How abnormal is the behaviour of captive, zoo-living, chimpanzees?” shows that abnormal behaviors are displayed by all 40 captive chimpanzees in accredited zoos observed for the study, that they spend an average of 4% of their day displaying abnormal behaviors, and that some individuals spend more than 60% of their days engaged in abnormal behaviors such as eating feces, rocking, plucking out their own and others’ hair, and many other behaviors never or very rarely seen in the wild. The study’s authors conclude, “Future research should address preventative or remedial actions, whether intervention is best aimed at the environment and/or the individual, and how to best monitor recovery. More critically, however, we need to understand how the chimpanzee mind copes with captivity, an issue with both scientific and welfare implications that will impact potential discussions concerning whether such species should be kept in captivity at all.”

![]()

In 2013, the NhRP began its fight for nonhuman rights with chimpanzees Tommy, Kiko, Hercules, and Leo as the organization’s first clients and Dr. Goodall on the NhRP’s board. Without rights, first and foremost the right to bodily liberty, these self-aware, autonomous beings remain legally vulnerable, and they deserve more than to be treated as legal things with no rights—with Tommy’s location unknown for years, Kiko forced to wear a chain and padlock around his neck, and Hercules and Leo, after spending the first years of their lives in a university lab where they were used in locomotion research, still denied daily outdoor access at Project Chimps (with some hope now for positive change).

Fortunately, courts are beginning to reject chimpanzees’ thinghood—for example, litigation modeled on the NhRP’s has freed a chimpanzee named Cecilia from an Argentine zoo to a sanctuary in recognition of her inherent rights, and in the NhRP’s chimpanzee rights cases, then New York Court of Appeals Judge Eugene Fahey wrote that the question of nonhuman animals’ legal personhood and rights constitutes “a deep dilemma of ethics and policy that demands our attention. To treat a chimpanzee as if he or she had no right to liberty protected by habeas corpus is to regard the chimpanzee as entirely lacking independent worth, as a mere resource for human use, a thing the value of which consists exclusively in its usefulness to others. Instead, we should consider whether a chimpanzee is an individual with inherent value who has the right to be treated with respect.”

There is nothing we can do to change the trajectory of Ham’s life. He lived and died at the mercy of human choices. But maybe there are things we can still do to honor him. We can tell his story, the one hidden beneath the proclamations about an intrepid space hero. We can invest in conservation and education for endangered wild populations of chimpanzees. We can encourage the NIH to reconsider whether the risks of transport and adjustment to life in sanctuary really outweigh the harms of being kept in biomedical research cages for the approximately eighty-five chimpanzees they deem too frail for sanctuary. And we can pursue legal rights for chimpanzees, so that when their autonomy is violated, we are able to defend them in court, not as damaged property, but as beings whose lives matter to them just as ours do to us.

![]()

Humans like to tout the vastness of space, how the ability to explore the universe beyond our planet gives us insight into ourselves and our world. Human astronauts have and will continue to assume great risks. Not all have survived. Each time, the decision to go into space, the risk they have assumed, has been their choice to make. The nonhuman animals had no choice about whether their bodies were strapped into deceleration sleds or placed into centrifuges and decompression chambers or launched into space. They have also not had the choice to stay with their families, to live free, outside of the confines of a cage, to choose their companions or how to spend the hours of their days. As we have expanded our horizons and our beliefs over what is possible, we have shrunk their worlds, from their rich lives in community with their families to barren cages, from days spent foraging and playing to days of confinement. Humans have walked on the moon, have lived on the International Space Station, are currently launching satellites that will bring internet to all parts of the world, and are planning to go to Mars, all because first, we imagined it was possible. Now imagine this. A future in which the value of nonhuman animals like Ham is not measured by their utility to humans, but instead a future in which they have rights, they have choices and are respected for the self-aware beings they are, that Ham was.

![]()

The Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) is the only civil rights organization in the United States dedicated solely to securing rights for nonhuman animals. Our work challenges an archaic, unjust legal status quo that views and treats all nonhuman animals as “things” with no rights. As with human rights, nonhuman rights are based on fundamental values and principles of justice such as liberty, autonomy, equality, and fairness. All of human history shows that the only way to truly protect human beings’ fundamental interests is to recognize their rights. It’s no different for nonhuman animals.