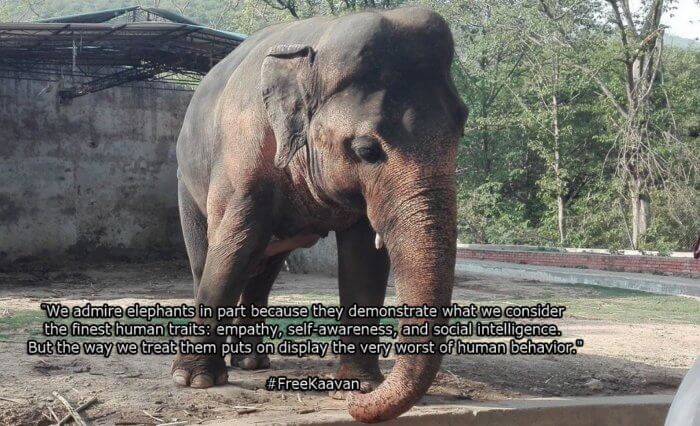

Currently in Pakistan there is an elephant named Kaavan. For the past three decades, since he was a baby of between one and two years old, he has been held in conditions not fitting for any being. Considered property, he was a diplomatic gift from the Sri Lankan government to the Pakistan government in 1985. Many people are aware of Kaavan and his story of being tightly chained almost his entire life in deplorable conditions in the Islamabad Zoo.

Thanks to the hard work of many people around the world, there has been a tremendous amount of activity to get his story into the public spotlight. It is in large part because of social media pressure alerting Pakistani senators, and no less than the Chair of the Senate of Pakistan, to Kaavan’s plight and forcing the local government in Islamabad, which owns Kaavan and manages the zoo, to address some of the conditions in which Kaavan lives.

Part of the misinformation that the zoo presented was that Kaavan had to be chained because he was dangerous. Now, thanks to public pressure, Kaavan is left unchained for longer periods of time, and he has proved them wrong—he is not dangerous.

The zoo owners, managers, and handlers/mahouts have been running this zoo for years with horrific standards of care. The Islamabad Zoo is well known for its consistently bad conditions; its disregard and abuse of numerous animals who are exposed to solitary confinement; extreme heat and extreme cold in inadequate shelter; nutritionally poor diets; punishment; and, in too many cases, avoidable illnesses and death. The animals are viewed as no more than disposable commodities.

Let’s go back to when Kaavan once had a companion elephant named Saheli. She was brought to the zoo in 1991, and after being sufficiently broken in, she was put to work giving rides and having pictures taken by paying customers. When she wasn’t working, she was chained alongside Kaavan. Saheli developed wounds on her legs probably due to chains cutting into her skin. In spite of zoo visitors noticing that Saheli had begun to limp and alerting the management, the zoo administration ignored the gravity of her condition. Finally on April 29, 2012, she collapsed. The zoo veterinarian, who is unqualified in elephant management and medical care, could do nothing for her. Clearly by this time it was too late, and Saheli died on May 1, 2012. Kaavan was chained beside her during her illness and collapse, and as she was hoisted out of the zoo by crane, reports say that he was highly disturbed.

Elephants like the NhRP’s clients Beulah, Karen, Minnie, and the elephant we have been fighting for in Pakistan, Kaavan, are captured from the wild and from their families. Herd members are very often killed in the process of trying to protect the babies. Traumatized babies are shipped from their native habitat to be physically abused and mentally “broken” until they submit to a life as a docile “attraction” of one sort or another in zoos or circuses, giving tourist rides, kept as status symbols, or owned or rented for religious and cultural festivals. All this is even worse when we consider that elephants are scientifically proven to be one of the most intelligent species on earth; they are highly social and form lifelong bonds, are known to show empathy, are body-aware, and many would argue, self-aware.

In 2016, specialists went to the Islamabad Zoo to assess Kaavan and reported that he exhibits ‘severe’ behaviors indicative of stress. No wonder, when his life has been so unnatural, and he has been forced to live much of it chained and unable to take even a step because the chains are so tight. He has suffered interminable years of violent physical abuse to control and train him, and, also like Beulah, Karen, and Minnie, this intelligent being is forced to live day-to-day with so little if any autonomy. His owners are permitted to keep him without attending to even his most basic medical and dietary needs. The recommendations of the specialists—that Kaavan needs veterinary supervision and treatment—have been ignored. There are many photographs and videos of Kaavan chained, obsessively rocking his head and torso, and being financially exploited by his handler.

One year ago, the Cambodia Wildlife Sanctuary kindly offered to give a home to Kaavan where he could live autonomously, over time shed his habitualised behaviours, receive appropriate expert medical care, and socialize if he chose to. We are still campaigning for this outcome, which would be at no cost to his owners. It is too late to release him in to the wild because humans have robbed him of the survival skills that he would have learned over the course of his life, but nothing less than an expertly managed sanctuary environment is appropriate for these captive sentient beings.

Arguments against captivity, born out of scientific evidence that even the best of zoos cannot provide sufficiently for elephants, are gaining traction, but we know that the majority of captive elephants worldwide are still held in grossly and systemically inadequate facilities which continually cause premature deaths, diseases, and long-term mental and physical suffering. That is why we need to recognize elephants’ nonhuman legal personhood and fundamental rights. As we continue to learn about elephants, we are increasingly aware that no standard captive environment can replicate an elephant’s complex needs and highly social lives; this includes males like Kaavan who are as social as female elephants—contrary to old beliefs and the continuing mantra of those who hold male elephants in isolated captivity. If we have to destroy the innate characteristics of a nonhuman animal in order to keep him captive, what is the point? As a human species we have failed miserably in this regard because legally and culturally we still view all animals as property.

In Pakistan there are no laws protecting wild animals’ captive in zoos. This litigation of the Nonhuman Rights Project is of great importance to all in recognizing that we need to move forward and protect this extraordinary species, and we believe that this can only be done appropriately through acknowledging that they should have certain rights.

In the introduction to Marjorie Spiegel’s book The Dreaded Comparison: Human and Animal Slavery (1988), Alice Walker writes that animals were no more created for humans than black people for white or women for men. We believe that elephants were not created for humans: they have their own right to exist in this world as they are naturally born to be, and as humans, we should enable them to do that.