Kiko

Kiko was a chimpanzee who was held in captivity in a cage in a storefront attached to the home of Carmen and Christie Presti in Niagara Falls, New York.

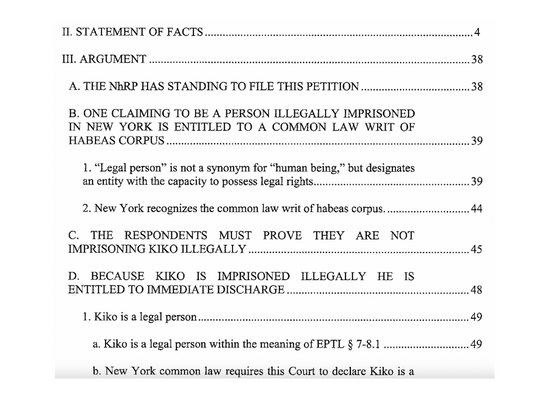

Originally “owned” by an exotic animal collector and trainer named Roger Figg, Kiko was at least partially deaf as a result of physical abuse he suffered on the set of the made-for-TV movie Tarzan in Manhattan. “[Kiko] bit an actor and was punished by having two trainers hold him while a third struck him on the head with a blunt instrument,” according to the Prestis.

The Prestis hold in captivity numerous other primates under the auspices of a tax-exempt non-profit corporation called The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., currently operated out of their home. For over a decade, they have cited their plans to build a larger facility in nearby Wilson, NY.

In photos, Kiko could be seen with a steel chain and padlock around his neck, which the Prestis appear to use as a leash.

The NhRP believes Kiko died in 2016 after spending years living in captivity. He experienced little freedom in life, but we know his story and court case will help ensure the future freedoms of other chimpanzees.

The NhRP attorney who argued for Kiko’s freedom

Our founder and president appeared before numerous New York courts to demand recognition of Kiko’s legal personhood and right to liberty. Some of these courts were sympathetic; some were downright hostile. With his decades of experience, Steve was prepared for both.

Who's joined us in the fight

Scientific and legal support

Dr. Jane Goodall was among the many chimpanzee experts who submitted affidavits in support of Kiko’s right to liberty. Kiko and Tommy’s cases were also the first in which philosophers and legal scholars submitted supportive “friend of the court” briefs.

Donate to support the fight

Donate online

Mail a check

611 Pennsylvania Ave SE #345

Washington, DC 20003

Planned giving

Create a fundraiser

Highlights from the fight

Media coverage

A timeline of Kiko’s case

2016

12.3.13

The NhRP files a petition for a common law writ of habeas corpus in New York State Supreme Court, Niagara County to demand recognition of Kiko’s right to liberty and release to a sanctuary. Read and download our Memorandum of Law and affidavits submitted by Steven M. Wise, Sarah Baeckler Davis, James R. Anderson, Christophe Boesch, Jennifer M.B. Fugate, Mary Lee Jensvold, James King, Tetsuro Matsuzawa, William C. McGrew, Mathias Osvath, and Emily Sue Savage-Rumbaugh.

12.9.18

New York State Supreme Court Justice Ralph A. Boniello III holds a hearing over the phone to allow the NhRP to place our arguments on the record. At the end of the hearing, Judge Boniello denies our habeas petition because he is “not prepared to make that leap of faith” but nevertheless wishes us luck.

10.10.14

The NhRP files a Notice of Appeal with the New York State Supreme Court, Appellate Division, Fourth Judicial Department. In the months that follow, Judge Boniello inexplicably refuses to “settle the record,” i.e. agree that the record was what we said it was, thus preventing the appeal from moving forward.

10.23.14

The NhRP seeks a petition for a writ of mandamus requiring Judge Boniello to rule on our request and/or settle the record. He does so after the Appellate Court schedules oral argument in Kiko’s case, enabling us to finally file our brief.

12.2.14

The Fourth Judicial Department holds a hearing in Rochester, NY. Oral argument lasts 20 minutes—twice as long as was scheduled. The five-judge panel asks insightful questions and repeatedly calls the NhRP’s expert affidavits “impressive.” Were the court to grant Kiko a writ of habeas corpus, NhRP President Steven M. Wise says during the hearing, “it would be the interests of Kiko that are being taken into account, not the interests of a person who calls himself his owner, and who has him with a chain around his neck in a cage.”

1.2.15

The Fourth Judicial Department denies our habeas petition, writing, “habeas corpus does not lie where a petitioner seeks only to change the conditions of confinement rather than the confinement itself.” In other words, the Court reasons that our use of habeas corpus is improper because we aren’t demanding Kiko’s absolute release, but rather, his transfer to an appropriate sanctuary. The ruling is good for the NhRP in other ways, however: first, the Court declines to rule on whether Kiko is a legal person but appears to assume at points that he is or could be. Second, the Court chooses not to adopt the Third Judicial Department’s Dec. 4 ruling in Tommy’s case (that chimpanzees can’t be persons because they can’t bear duties and responsibilities), which shows the New York courts are far from united in their (erroneous) reasoning for denying personhood and rights.

1.15.15

The NhRP files a motion seeking permission from the Fourth Judicial Department to appeal to New York’s highest court, the Court of Appeals. As we assert, the Fourth Judicial Department’s decision directly conflicts with two centuries of New York decisions that show that immediate release via a writ of habeas corpus pertains to release from unlawful confinement and doesn’t prevent an individual from being lawfully transferred elsewhere.

3.20.15

The Fourth Judicial Department denies the NhRP’s motion.

4.10.15

The NhRP seeks permission to appeal directly to the Court of Appeals.

9.1.15

The Court of Appeals denies the NhRP’s motion. “While disappointed in the Court of Appeals’ decision today denying our motions for leave to further appeal in both Tommy’s and Kiko’s cases,” says NhRP President Steven M. Wise in an official statement, “we are in no way discouraged.”

1.7.16

The NhRP files a new habeas petition in New York State Supreme Court, New York County to again demand Kiko’s release from unlawful detention. Court filings include a revised Memorandum of Law and 60 additional pages of expert affidavits submitted by Jane Goodall, James R. Anderson, Christophe Boesch, Mary Lee Jensvold, William C. McGrew, and Sue Savage-Rumbaugh. Together, these documents demonstrate that chimpanzees can and do bear duties and responsibilities.

1.29.16

New York County Supreme Court Justice Barbara Jaffe denies the NhRP’s second habeas petition on the grounds that our new filings don’t warrant further action from the Court.

5.17.16

The NhRP files an appeal of this denial in the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, First Judicial Department. The First Judicial Department Clerk’s Office subsequently contacts the NhRP’s counsel to inform us that we don’t have a proper order from which an appeal can be taken and that we don’t have an appeal as of right from the lower court’s refusal to issue the order to show cause or writ of habeas corpus.

5.20.16

The NhRP requests that the lower court enter an appropriate order from which an appeal may be taken, which the Court issues the same day.

5.26.16

The NhRP files a Motion to Appeal as of Right with the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, First Judicial Department.

7.5.16

The NhRP files a motion with the lower court for an order stating that the final order of 5.20.16 be issued nunc pro tunc to the original order of 1.29.16, which the Court grants the following day.

7.28.16

Justice Troy K. Webber of the First Judicial Department enters an order in which she sua sponte converts the NhRP’s Motion to Appeal as of Right into a Motion for Leave to Appeal, then denies this motion, which we neither filed nor intended to file (knowing we have an absolute right to appeal under Article 70 of the New York Civil Practice Law and Rules), nor were we given the opportunity to oppose it.

8.19.16

The NhRP files with the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, First Judicial Department a Motion to Reargue or, alternatively, for Leave to Appeal to the Court of Appeals from the 7.28.16 order.

10.25.16

The First Judicial Department denies the NhRP’s Motion to Reargue.

11.1.16

11.10.16

The First Judicial Department affirms the NhRP’s absolute right to appeal from the lower court’s 1.29.16 refusal to issue a writ of habeas corpus or order to show cause on behalf of Kiko. “We never doubted that we had an absolute right to appeal the lower court’s decision and are delighted that, after nearly a year of litigation, the Court has recognized our absolute right to appeal on behalf of Kiko,” says NhRP President Steven M. Wise in an official statement.

12.5.16

Legal scholars Justin Marceau, Professor Of Constitutional and Criminal Law at University Of Denver Sturm College Of Law, and Samuel R. Wiseman, Professor of Constitutional and Criminal Law at Florida State University College Of Law, request leave to file an amicus curiae brief in support of the NhRP in Kiko’s case. In the brief, they exhort the Court to allow Kiko to use habeas corpus to challenge the legality of their detention just as other “unjustly incarcerated beings” have done throughout history. Of particular relevance, they note, is use of the writ by innocent human beings imprisoned for crimes they did not commit:

“Nonhuman animals are unquestionably innocent. Their confinement, at least in some cases, is uniquely depraved; and their cognitive functioning and their cognitive harm as a consequence of this imprisonment, is similar to that of human beings.”

12.7.16

Legal scholar Laurence H. Tribe, Carl M. Loeb University Professor and Professional of Constitutional Law at Harvard University, requests leave to file an amicus curiae brief in support of the NhRP in Tommy’s case. In the brief, Tribe urges the court to consider Tommy’s case on the merits and “recognize that he is an autonomous being who is currently detained and who is therefore entitled to challenge the lawfulness of his detention by petitioning for the writ, even if that court ultimately concludes that [their] detention is lawful.”

The NhRP requests leave to file a reply to an amicus curiae brief filed 11.29.16 by Pepperdine University Law Professor Richard L. Cupp, Jr. with the First Judicial Department. Cupp “offers neither science nor law to support his positions” and reasons from a flawed understanding of the meaning of the social contract and how the common law evolves, the NhRP argues. Replies to amicus briefs aren’t common, and courts have ample latitude to ignore them, but we file one nevertheless because Cupp’s arguments far exceed the purpose of such a brief, in our view.

1.3.17

The First Judicial Department denies the NhRP leave to file a reply to Cupp’s brief and grants leave to Tribe and Marceau and Wiseman to file their amicus briefs.

3.16.17

In a joint hearing for Tommy and Kiko in Manhattan, NhRP President Steven M. Wise argues that the capacity to bear duties and responsibilities isn’t a legally acceptable reason for denying recognition of Tommy’s and Kiko’s legal personhood and fundamental right to bodily liberty. Requiring this capacity as a precondition for personhood “[would deprive] millions of humans in New York the ability to go into court” under habeas corpus, a reference to infants, children, incapacitated and elderly people who cannot realistically fulfill this requirement. Wise points out that chimpanzees can bear duties and responsibilities within their communities and says claiming otherwise is “biased and arbitrary.” The Third Department ruling was “irrational,” he tells the court, citing Tribe’s amicus brief. “It was unfair, and it’s not backed up by science.”

3.27.17

The NhRP delivers a letter to the First Judicial Department to notify the Court of 1) a recent ruling in Mohd. Salim v. State of Uttarakhand & Others that recognizes two rivers as legal persons with fundamental legal rights 2) the publication of a law review article that critiques the Third Judicial Department’s ruling in Tommy’s case and 3) a significant error in Black’s Law Dictionary regarding the definition of a legal person. According to the most recent edition of Black’s Law Dictionary, a “person” must have the capacity to bear “rights and duties.” However, the source on which the the definition is based actually states that “a person is any being whom the law recognizes as being capable of rights or duties.” The Third Judicial Department relied on the erroneous definition to deny personhood to Tommy the chimpanzee in 2014.

4.6.17

NhRP Executive Director Kevin Schneider emails the editor-in-chief of Black’s Law Dictionary, Bryan Garner, to notify him of the error and urge him to correct it. In an email sent in response, Garner thanks Schneider for drawing the error to his attention and writes that he has “marked it for correction in the [next] edition.”

4.11.17

The NhRP files a motion seeking leave from the First Judicial Department to file the NhRP’s letter and Garner’s reply for consideration in Kiko’s case.

6.6.17

6.8.17

6.22.17

The NhRP publishes a fully annotated version of the First Judicial Department’s decision, pointing out how and why it’s legally wrong.

11.6.17

The NhRP files a motion with the First Judicial Department for permission to appeal to New York’s highest court, the Court of Appeals, in Tommy’s and Kiko’s cases. Read the accompanying Memorandum of Law here.

1.8.18

The First Judicial Department denies our motion for permission to appeal. Within the next 30 days, the NhRP will file a motion for permission to appeal with the Court of Appeals itself, urging it to reject the First Judicial Department’s erroneous approach to our common law habeas corpus cases and to engage in the mature weighing of public policy and moral principle these novel and complex legal issues demand.

2.26.18

The NhRP announces it has filed a motion for permission to appeal to the New York Court of Appeals in Tommy’s and Kiko’s cases, and a group of prominent philosophers submit an amicus curiae brief in support. The NhRP argues in its Memorandum of Law that the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, First Judicial Department’s June 2017 ruling requires review by the state’s highest court, not only because it conflicts with New York’s common law habeas corpus statute and previous rulings of the Court of Appeals, the First Department, and other Appellate Departments on issues pertaining to common law personhood and habeas corpus relief, but also “based on the novelty, difficulty, importance, and effect of the legal and public policy issues raised.” Engaging directly with a core issue raised by the NhRP’s appeal—the question of who is a “person” capable of possessing any legal rights—the philosophers’ brief maintains that the First Department’s ruling “uses a number of incompatible conceptions of person which, when properly understood, are either philosophically inadequate or in fact compatible with Kiko and Tommy’s personhood.”

3.8.18

The NhRP announces that legal advocacy organization the Center for Constitutional Rights and law professors Laurence H. Tribe, Justin Marceau, and Samuel R. Wiseman have submitted amicus curiae briefs in support of the NhRP’s motion for permission to appeal.

5.8.18

The New York Court of Appeals denies our motion for permission to appeal, and New York Court of Appeals Judge Eugene M. Fahey issues a concurring opinion in which he asserts that the failure of the Court to grapple with the issues the NhRP raises “amounts to a refusal to confront a manifest injustice … To treat a chimpanzee as if he or she had no right to liberty protected by habeas corpus is to regard the chimpanzee as entirely lacking independent worth, as a mere resource for human use, a thing the value of which consists exclusively in its usefulness to others. Instead, we should consider whether a chimpanzee is an individual with inherent value who has the right to be treated with respect.”

Judge Fahey concludes his opinion with a striking personal reflection: “In the interval since we first denied leave to the Nonhuman Rights Project, I have struggled with whether this was the right decision. Although I concur in the Court’s decision to deny leave to appeal now, I continue to question whether the Court was right to deny leave in the first instance. The issue whether a nonhuman animal has a fundamental right to liberty protected by the writ of habeas corpus is profound and far-reaching. It speaks to our relationship with all the life around us. Ultimately, we will not be able to ignore it. While it may be arguable that a chimpanzee is not a ‘person,’ there is no doubt that it is not merely a thing.”

Judge Fahey’s opinion is believed to be the first time a Court of Appeals judge has issued a separate opinion on a motion before the Court.

Amicus Support